A behind the scenes look at the server in the MessageWeek office.

(Filmed on an HTC Velocity 4G SmartPhone. Not our usual camera, of course, but very convenient for video blogging).

Godly conversations

A behind the scenes look at the server in the MessageWeek office.

(Filmed on an HTC Velocity 4G SmartPhone. Not our usual camera, of course, but very convenient for video blogging).

The Book of Acts carefully describes the emergence of the primitive early church following the coming of the Holy Spirit on the Day of Pentecost. The 28 chapters of Acts convey the activity, issues, personalities, teachings and sermons of various apostles, including detailed narration of the presence and power of the Holy Spirit working through Peter and John manifesting itself in a variety of miracles, the wisdom of James, and the travels and episodes in Paul’s ministry. Roman rulers are mentioned by name, as are cities and geographic areas.

Thus Christians reading the Book of Acts today are given a good description of the beginnings of Christianity as lived through the emergence of the early church. We read of the issues surrounding the Gentiles being given the Holy Spirit in a climate of Jewish opposition. We read of Jewish insistence for new converts to be circumcised and the resulting Jerusalem apostolic conference that discussed the giving of the Holy Spirit to the Gentiles and their resulting edict. We read descriptions of various Roman rulers who encountered the gospel via Paul’s testimony. We wonder at the manifestation of the Holy Spirit through numerous amazing miracles, such as Paul and Silas, and well as Peter, being freed from prisons, of healings, and of accurate prophecies such as given by Agabus. We weigh in on the problems and issues of the church some 2000 years ago, and cannot help but ponder how the Acts narrative might edify the modern church today.

Do the times and circumstances of some 2000 years ago as recorded in Acts, the incidents that occurred and resulting judgment calls, as well events tied to an ancient calendar, help us navigate our theology today? If Acts is purely descriptive and belonging entirely to another age, then we can simply see the book purely in a more or less a historical focus. Viewing Acts through an exclusively historical lens would then help us understand that Luke’s recording of the remarkable miracles of healing, freeing from prison, visitation by angels, and visions from God only existed in the context of those times, and are not necessarily to be expected in the Christian experience today.

And yet, we’re also confronted by the issue of being edified by what the early Christians believed, and how they applied their understanding to everyday life. Do the overall experiences and outcomes of early Christian practise and theology as cited in Acts carry any prescriptive weight for us today – in the light of Paul’s prescriptive comment in 1 Corinthians 11:1 when he said, “Imitate me, just as I also imitate Christ.”?

I believe that Acts is not only a descriptive historical narration containing elements that cannot be repeated in today’s Christian experience, such as witnessing Jesus’ ascension, or worshipping at the Jewish temple in Jerusalem (Elewell, Yarbrough Encountering the New Testament, Baker Academic, 2008, 212), but that it also speaks to us on a prescriptive level that mirrors core doctrinal teachings supported elsewhere in scripture. For example, Paul’s belief in the resurrection of Jesus and his actively preaching of the resurrection is supported elsewhere in the New Testament.

The challenge is: how far do we apply the prescriptive element contained in Acts in our faith and practise today? For example, many in our community of believers acknowledge Luke’s interesting inclusion of certain usually-relegated-as Jewish days of worship. The modern reader of Acts notes that the Holy Spirit came on the Day of Pentecost, which we believe was a Sunday morning. Why were the disciples gathered in a meeting place on that Sunday? Had the weekly day of worship and fellowship changed from Sabbath to Sunday? The disciples were indeed gathered in “holy convocation” on this Holyday known as Pentecost, as they had perhaps always done. Of note is that God chose to use the significance of this day, historically believed to be when God originally gave the ancient Israelites the Ten Commandments, to now abundantly pour out the Holy Spirit on all who believed.

Luke also mentions Paul’s insistence to keep a certain feast:

When they asked him to stay a longer time with them, he did not consent, but took leave of them, saying, “I must by all means keep this coming feast in Jerusalem; but I will return again to you, God willing. “And he sailed from Ephesus. (Acts 18:20-21)

Can we take any bearings from Paul’s insistence on keeping this feast, be it Unleavened Bread or Tabernacles? Is this simply descriptive, or is it prescriptive? Luke also mentions the Fast, a reference believed to be the Day of Atonement (Acts 27:9). Elsewhere, Luke also importantly mentioned that they sailed after the Days of Unleavened Bread (Acts20:6) and from this the reader can understand that there were presiding reasons not to sail until Unleavened Bread was completed. The next verse (7) refers to an assembly [correctly translated] “the first of the Sabbaths”. This was not a Sunday assembly, but an assembly on the first of the seven Sabbaths (or weeks) counted from Unleavened Bread to Pentecost. [New Testament Greek does not have a word for “week”; the word for week occurs in the Septuagint and in modern Greek].

Theologians acknowledge that the interpretive understanding gleaned from the above examples are often hotly debated, especially by those who disagree with the implications that these Holydays bear relevance to the Christian today, it nonetheless demonstrates the interpretive challenges that Acts presents. (Elewell, Yarbrough, Encountering the New Testament, Baker Academic, 2008, 213)

The Book of Acts is a necessary part of the Biblical canon. It details the early church as it tried to follow the teachings of Jesus Christ; it documents firstly the work of the Peter, John and James, and devotes the final two thirds to Paul’s journeys and experiences; it documents the entrance of Gentiles into the faith, and it also gives us a good insight into what our Christian forefathers believed and how they applied that understanding. In this Acts still speaks to us today, not only as a historical narrative, but also fleshing out the prescriptive element, instructions on how to live the new life in Christ.

John Classic

Written for LifeSpring

It’s hard to elevate one of the Gospel accounts above the others, as they each give testimony in their own way to the Messiah. In some ways, however, we’re indebted to Luke for his account. Not being a personal witness of Jesus, Luke nonetheless acknowledges others who have undertaken to write an account of what happened.

Thus Luke, an educated Gentile who practised as a doctor, set out to write an orderly account of what actually happened for the benefit of his benefactor, Theophilus.

Luke’s Gospel contains information that the other accounts do not. For example, Luke gives a lot of information about the events and circumstances leading up to the birth of Jesus, and we can only presume that Luke, as Paul’s travelling companion, took the time when in Judea to speak personally and listen to Mary’s personal testimony. (WA Elwell, RW Yarbrough, Encountering the New Testament, Page 102, Baker Academic, 2005). Thus the events of Jesus’ early life are carefully and well documented.

Like Matthew, Luke also gives a genealogy of Jesus Christ, but Luke goes further back before Abraham (where Matthew began) and links Jesus Christ to Adam, who was the son of God.

Speculation as to when Luke wrote his gospel account varies depending on different theological schools of thought on this. We must remember that Luke also wrote Acts and the timing of this second book affects when Luke wrote his original treatise – which would have to have been sometime and probably in the decade before the fall of Jerusalem in 70AD. Agreement on the place of writing is also speculative, as Luke does not principally identify this. Luke’s writing stands out above the gospels in its literary style, reflecting an educated and mature man well versed in the classical Greek language of his day.

Luke’s gospel is unique in perhaps more than one way. For example, Luke gives the reader special attention and appreciation for how Jesus honoured and respected women; the personal details of women in Jesus’ ministry are clearly remembered. For example, an incident is recorded where the disciples wondered why Jesus would speak to a Samaritan woman at the well. Another notable incident was when the woman who was healed simply because her faith led her to anonymously touch the hem of Jesus’ garment. Luke also mentions the women in Jesus’ ministry by name and their unique circumstances. For example, Luke tells us of Mary Magdalene and the curing in her life, as well Joanna’s unique disposition.

Luke pays special attention to the ministry of the Holy Spirit, right from the conception of Jesus, through the work of John the Baptist, what Jesus said of the Holy Spirit, and how he lived his life as encapsulated in the phrase “full of joy through the Holy Spirit…” (Luke 10:21) Thus the historical Jesus is also conveyed with an overt theological overlay.

We must remember that Luke’s account was not written from a born and bred Hebrew perspective, as the others authors were. Luke was a Gentile, a Greek as we might understand it, and his writing helps the reader understand that the good news of salvation in Jesus Christ isn’t restricted to ethnicity but is available to all people. Thus if Luke’s account had been destroyed by the sands of time, we would be so much the less wiser; the critical details of Mary and Elizabeth’s relationship and conversation, for example, would have been lost. Thus Luke’s work miraculously stands the test of time; he is a worthy historian and in doing so captures the spirit of the early, pioneering followers of Jesus.

By John Klassek

For LifeSpring School of Ministry

A Christian is a follower of Jesus Christ, called by God the Father and brought to understanding through the work and presence of the Holy Spirit. Thus the only authoritative source we have that tells us of Jesus is the Bible, and specifically the New Testament account containing 27 books written in the first century by those who personally experienced Jesus Christ and others who came to believe through their ministry.

Thus to live a Christian life without a careful personal enquiry into who Jesus was, what happened to him, and how we might come to a fuller understanding and appreciation of God’s love and purpose for all people, would be to intentionally live a life of ignorance. Thus all followers of Jesus are compelled to varying degrees to personally explore those scriptures. Those who were illiterate in the first century benefitted from the weekly scripture readings at the Synagogue; the emerging Christian community is believed to have continued the tradition of Sabbath scripture readings, and we have reason to believe that the letters of Paul, for example, were also read to the churches. (Colossians 4:16, 1 Thessalonians 5:27)

Today the western world (at least) benefits from a high degree of literacy, and via the mechanism of mass printing as well as digital technology, we have the written Biblical text more available than ever before. Now while we could erroneously assume that a cursory view of the New Testament might be sufficient to adequately know the basics of God’s word, we would unfortunately then be highly susceptible to viewing and interpreting the New Testament through our own culture and personal experiences, or at worst, allow a mystical-flavoured perception and understanding to persist that assumes that the Holy Spirit as counsellor is sufficient without informed personal study.

This then leads to the question: how do we study the scriptures, especially the New Testament, and by which methods can we best benefit? Is a specific historical study sufficient?

Historical-Criticism approaches the Biblical text from a non-faith perspective, whereas Historical-Theological Criticism begins with the premise that the scriptures are indeed “God breathed” (2 Timothy 3:16), that men wrote from their eye-witness and personal experiences and understanding as inspired by the Holy Spirit. While Historical-Criticism may be valuable in understanding, for example, the Jewishness of Jesus in the times and culture where he lived, (Encountering the New Testament, WA Elwell, RW Yarbrough, Page 156), the method treats the Biblical text as it would any other book and in doing so negates the influence of God’s Holy Spirit.

In then attempting to interpret and understand the New Testament account for what it presents itself as: eyewitness accounts of Jesus as well as the documentation of the emergence of the early Christian community, we come across the term “hermeneutics” – which simply is the theory and practice of interpretation. (Encountering the New Testament, WA Elwell, RW Yarbrough, Page 159).

The work of interpretation involves our personal underlying purpose for undertaking it. What are our aims – is it to discredit the text or to gain further understanding; am I studying for personal devotion or to prepare a sermon? What are the conditions we employ for engaging the text – does the reader believe in the aiding role of the Holy Spirit or is viewing the text purely from an historical perspective? How do we begin, that is, what method will we apply – do we randomly turn to any page and start reading, or is there a systematic approach, perhaps aided by a planned reading from cover to cover as well as utilising supplementary Bible commentaries and handbooks?

Hermeneutics, if it is to be successful and enduring, must be based on the following premises: that the Bible is the inspired word of God as written by human agents. The Bible having been preserved down through the ages as an act of God’s divine will, presents itself today as the world’s most printed and published book ever, speaking to us of God, who He is, what He is doing, and what His plans are. A serious student of the Bible “enters into the text” by a careful reading, is dedicated to analysing its content and seeks to find authentic application for today’s living, and this also involves giving heed to its prophetic content and direction. Thus the New Testament in particular is “both history and theology simultaneously”. (Encountering the New Testament, WA Elwell, RW Yarbrough, Page 165, Summary).

If we are to benefit most from what the scriptures are, we’ll see that the New Testament is founded on the background and preparation that the Old Testament gives, that the gospels are genuine eyewitness and research accounts of Jesus the Messiah, that Acts documents the emergence of the Church age (beginning specifically on the Day of Pentecost that heralded the coming of the Holy Spirit), that the Epistles (letters written to various churches and individuals) further document the issues that affected and the circumstances of the first century church, and finally that the text concludes on a counselling and prophetic note as contained in Revelation.

A core part of Hermeneutics in our study of the Bible must involve prayer. Prayer is the intentional two-way and private communion between God the Father and the believer. The believer believes God exists and that He actively sustains the created order; that this world is God’s realm, and that our only hope in life is through Jesus Christ. Prayer can involve active and specific petition, asking God for guidance and understanding in our study of the scriptures – and then believing in faith that God will respond in His time and way. The act of prayer is then further validated when the believer (the student of the Bible) then takes time to carefully consider what he or she is reading, when and by whom it was penned, in the diverse and distant cultural milieu those events formed, and the original purpose the author had in mind. Helps such as different translations, Bible concordances and handbooks can be a valuable aid in this study.

By John Klassek

Scientists predict that in approximately four billion years’ time, the sun will run out of the hydrogen that fuels it. As a result of the enormous gravitational pull inward, it will begin to collapse in on itself. The sun will then reach a point of critical mass, whereupon it will expand to become a red giant, and in doing so destroy not only the earth but the entire solar system.

The Bible also predicts that one day the earth will be destroyed by fire. God says that beyond that there will be a new heaven and new earth.

What does this have to do with the Sabbath? It’s all about time.

The weekly Sabbath rest is more than just a reminder that as physical humans we’re bound by constraints of space and time. It’s about holiness, it’s about REST, and it’s about being at one with God.

When this earth, as we know it, no longer exists, neither will the current parameters of days and nights, weeks, months or the years that help govern our passage through time.

At the beginning of the known era of humanity, there are two things that are intriguing in the Genesis account of creation.

Firstly, mankind was created after God’s own “image and likeness”. Thus, we were made with a capacity for relationships, were made to be creative, to have hopes and dreams. In other words, we have a mind that compares to nothing else in the known created world.

And, secondly, the creation week was concluded by the Great God (who doesn’t weary) by resting from all the work He had done. He set the seventh day apart, and made it holy. Later, Jesus Christ would give greater insight into why this was.

One of the things we learn from the creation week is that we’re moulded after the Godkind. One particular and obvious difference, however, is that, unlike God, we’re bound by the constraints of time and space, and as God told Adam and Eve, they would one day “surely die”. It was God who instituted a seven-day cyclic pattern at the beginning of the “human era” to assist, it seems, in marking the passing of time. But with that passing of time God included an “escape clause” picturing rest, for God told Adam (and Eve in similar manner after they had sinned) that his life would be characterised by labour — by the sweat of the brow, and further depicted by “thorns and thistles” (Gen. 3:17-19).

This was fascinating material and a road of discovery for a young boy growing up in one of the Churches of God. The passing of time, as marked by the weekly, seventh day Sabbath rest, was celebrated in our family home by a special Friday-night mealtime. Mum would cook a special dinner, using shiny cutlery and our finest crockery. Sometimes she would place a small vase with some fresh flowers from her extensive garden. Dad would offer us children a small glass of wine. He also rehearsed a point that Jesus had made: that “the Sabbath was made for man” (and not just for the Jews). (Mark 2:27)

Thus each passing week the Sabbath would be a natural reminder that God had created everything, and that along with our toil He promises us rest. When the Ten Commandments were given to ancient Israel, God again reminded his people about the creation of the Sabbath at the beginning of the human era. “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy,” God said. Then God elaborated: “For in six days the LORD made the heavens and the earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but he rested on the seventh day. Therefore the LORD blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy.” (Exodus 20:11)

Despite the toil in our often mundane routine of earning a living, God wanted mankind to taste, to appreciate and to value the concept of rest. Jesus’ compelling words ring out for all time when He exemplified the Sabbath rest by saying: “Come to me all ye who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.”

In time, I also learned what God accomplished through the coming of Jesus Christ. I learned about the spiritual rest found only in Jesus. I learned that all things have their fulfillment in Him. And as a result I benefitted enormously from the anticipated weekly time of rest, worship and fellowship. The Sabbath became recognised in our family not as some kind of legalistic old covenant appendage, but as a treasured gift of the Lord, breaking the yoke of slavery. The words “Thy Kingdom come…” often fittingly featured in Sabbath evening prayer. There was a yearning in our hearts for the passing of time, when the ultimate rest for all mankind would be fulfilled.

Then it was with interest that I read of Jesus’ encounters with the misled Pharasaical application of the law. The Jews in their zeal had turned a day of rest into a burdensome day, thus missing the point of what true rest was all about. Today, we live with the opposite extreme in our western society: there is little demarcation between the holy and the profane. (But that’s another subject altogether).

Jesus chose the Sabbath on several occasions to confront the Jewish religious leaders. He said that “the Son of Man is Lord of the Sabbath” (Matthew 12:8), and that it is “lawful to do good on the Sabbath.” He used their own limited understanding of law to chastise their hard-heartedness and blindness.

The Pharisees reasoned that He could have chosen any other day of the week to heal; on one occasion we read where He asked those (critically) watching Him whether “it is lawful to heal on the Sabbath.” Jesus chose to heal, to bring rest to those “in bondage,” within the framework of the Sabbath. In one reference to healing on the Sabbath day, He said: “My Father is working, and I must do the will of Him who sent me.”

The Sabbath rest as exprienced in the Churches of God today is all about Jesus Christ and His work. It was made by Him, it foreshadowed Him, it represents Him, and it exemplifies His work and will. The Sabbath can be an expression of Christ-centredness. In today’s frenetic, secular lifestyle, it can also be a dynamic part of discipleship: being prepared to forego all and follow Christ, whatever the cost, whether it be social life, weekend sports, or work. It’s a recognition that enjoying an extra special Friday-night meal as an expression of God’s love to your family amidst the fine food, laughter, learning, and the rehearsed hope of a better world.

The Sabbath rest is a gift of the Lord. It’s a gift to man. It marks the passing of time, but more than that, it points us to a time yet future when holiness will transcend all, and all will find rest.

Regarding the future of the cyclic hours and days, months and seasons, which include the weekly Sabbath, Jesus Himself tells us that one day there will be no night, with no need for the sun or moon, for the old (current) earth and heaven will have ceased to be (Revelation 21). We gain a glimpse that there will be a new earth and a new heaven where God Himself will be the light. The old sun and the solar system of which the earth is now a part will have long been forgotten. At that time the physical Sabbath rest will have finally served its purpose, and we gain a glimpse of this time from the writings of a prophet of old on this subject:

“As the new heavens and the new earth that I make will endure before me,” declares the LORD, “so will your name and descendants endure. From one New Moon to another and from one Sabbath to another, all mankind will come and bow down before me,” says the LORD. (Isaiah 66:22-23 NIV)

Written by John T Klassek

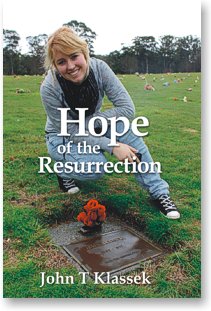

We would like to offer you a new, free book titled “Hope of the Resurrection”. Published just this month, there’s no cost, no follow up, just our gift to you. You may also like to watch a short interview that provides a little background to the book. http://www.message7.org/2010/bookresu_yt.htm

The “Hope of the Resurrection” is currently in its first edition. It is an easy-to-read book that simply asks those big questions: What does the Bible say about it, what did Jesus teach about it, and how did the first Christians understand and articulate this hope?

The “Hope of the Resurrection” is currently in its first edition. It is an easy-to-read book that simply asks those big questions: What does the Bible say about it, what did Jesus teach about it, and how did the first Christians understand and articulate this hope?

We hope you enjoy reading it, and that you’re encouraged and inspired to embrace the best news we could ever hear.

John Klassek

PS Let us know your comments. We’d love to hear from you.

A friend recently asked me whether Christians should keep the feasts as found in the Bible?

A friend recently asked me whether Christians should keep the feasts as found in the Bible?

The question perhaps might be rephrased, asking is there any value in Christians celebrating the “feasts of the Lord”? Let’s look at them briefly:

These “shadows” or metaphors of what God is doing through time in Christ are without doubt of extraordinary value to followers of Jesus today. They are gifts He makes available to us that mark God’s appointments in time, “moeds” that can help intelligently flavour our walk with God today. I doubt whether the ancient Israelites really had any idea of what they were celebrating on those annual occasions – God simply commanded them to do it, saying “These are my appointed feasts.”

Within our community of believers, whether one eats meat or doesn’t, drinks wine or doesn’t, or celebrates at the feasts or doesn’t, we love each other and deeply care for each other so as not to offend – while at the same time never compromising on the pillars of our faith. Thus the body of Christ is strengthened by the grace and love we extend to each other.

See you at the “feasts of the Lord”.

John Klassek

Over the past couple of year I’ve been working on a new book titled “Hope of the Resurrection”. The book is all but complete, and currently undergoing its final proof reading prior to printing. It is an easy-to-read book that we hope will find its way into the hands of millions of everyday people; its message, as its title implies, discusses the best news we could ever understand.

Over the past couple of year I’ve been working on a new book titled “Hope of the Resurrection”. The book is all but complete, and currently undergoing its final proof reading prior to printing. It is an easy-to-read book that we hope will find its way into the hands of millions of everyday people; its message, as its title implies, discusses the best news we could ever understand.

John Klassek